The Bizarre Phenomenon of 'Ball Lightning' Has a Startling New Explanation

As far as mysteries of nature go, ball lightning is one of the more perplexing. It seems there are as many potential explanations as there are sightings, but in spite of decades of intense interest, none stand out as a clear winner.

One of the weirder hypotheses claims these glowing balls are nothing more than light trapped inside a sphere of thin air. A new paper has added fresh details to the proposal, setting physical parameters on what such a light bubble might be like.

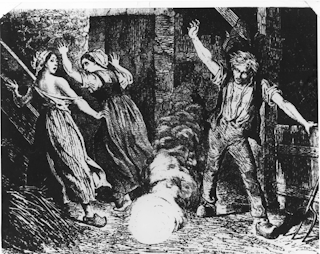

For centuries, people have recorded accounts of grape-fruit-sized orbs of light moving slowly a short distance above the ground, often in the middle of an electrical storm, persisting for maybe 10 seconds or so before silently winking out of existence.

Occasionally there is an added effect or two. Some have been said to pass through the glass pane of a closed window. Others might go out with a bang, or even leave behind the stench of sulphur as they vanish.

Over a decade ago, Vladimir Torchigin from the Russian Academy of Sciences came to the conclusion that the atmospheric phenomenon we call ball lightning isn't lightning at all, but rather photons ricocheting inside an air-bubble of their own making.

Whatever ball lightning happens to be, though, history isn't short on eyewitness reports.

Pulling apart myth from facts isn't easy, however, and in the past they were treated with a generous dose of scepticism. Today, researchers are cautiously optimistic that there's probably something to the multitude of observations.

In the 1970s, ball lightning researcher Stanley Singer suggested there were three essential features any successful model explaining the phenomenon had to account for; the duration of ball lightning, its floating motion, and its sudden disappearance.

Just a few years ago, an alleged event of ball lightning in China was by chance captured on a spectrograph following a lightning bolt striking the ground, providing researchers with a breakdown of its electromagnetic spectrum.

The research backs up an explanation by University of Canterbury engineer John Abrahamson, who suggested the glowing air could be the result of vaporised ground material being pushed up by a shockwave of air.

Other suggestions imagine clouds of charge-repulsing ions collecting on an insulator such as a glass sheet, providing a basis for the long life spans as well as drifting and 'bouncing' movements.

Torchigin's idea is as simple as it is highly speculative. It has nothing to do with charged ions, and everything to do with the intense shower of photons shed by a bright flash inside our atmosphere.

As any particle absorbs and emits electromagnetic radiation, there is a recoil referred to as the Abraham-Lorentz force. In theory, light spilling from a lightning strike causes air particles to jiggle as they absorb and transmit electromagnetic radiation.

This force isn't all that impressive under most circumstances, as even Torchigin admits by stating, "[t]hese forces are extremely small for conventional intensities of light, and their action is rightly ignored".

But the extreme intensity of a lightning strike isn't your normal flash. What's more, these optical forces could potentially be magnified considerably under the right conditions.

Those 'right conditions', according to Torchigin, involve the generation of a thin layer of air that refracts the light back in on itself.

A thin layer of air – not unlike the film of a bubble – could effectively focus light like a lens, intensifying the light enough to shove air particles into a boundary and produce a long-lived bubble, concentrating photons for seconds at a time.

Not all ball lightning 'embryos' would be successful, fading immediately for want of light or a sufficiently closed shell. But those that did hang around would look spectacular as they bobbed a haunting path through virtually any transparent medium.

The idea has been kicked around by Vladimir and his Russian Academy of Sciences colleague Alexander Torchigin in dozens of papers over the years.

Vladimir's most recent discussion on the topic combines numerous assumptions with physical models to pin down the light density and air pressure required to produce a suitable refraction index.

This might not explain some of the more violent endings to ball lightning, or the spectroscopic observations like those captured in China, or even necessarily the sulphurous smells.

But it does provide some numbers that could lead to necessary experiments that either rule out the hypothesis or give it an empirical backbone.

It's entirely possible Torchigin's idea is itself a lot of hot air, of course. But until we have a consensus on what might be behind those spooky, glowing spheres, it'll remain one of the more interesting contenders for a ball lightning theory.

This research was published in Optik.

Ball lightning exists ... but what on Earth is it?

It’s been seen by hundreds of people for hundreds of years in almost every country of the world – but has remained something of a mystery. Put simply, we don’t know what it is, what provides its energy, or why it moves independently of any breeze.

But my colleagues and I have published a new paper that should shed some light on this mysterious phenomenon and bring us one step closer to understanding, definitively, what ball lightning is.

A bright history

My association with ball lightning began in the 1960s when I was working for Westinghouse Research Laboratories in Pittsburgh in the USA – working on the theory of cooling air formed from electric arcs in circuit breakers.

Next to my office was the office of physicist Martin Uman who now, having written three text books on lightning, is regarded as the world’s leading lightning scientist.

One day, over coffee, Martin mentioned that ball lightning was one of the very few phenomena we don’t understand at all, despite having been seen by hundreds, maybe thousands of people.

I replied that I thought ball lightning was just hot air produced from a lightning strike – the ball of hot air being so large that it cooled only slowly, giving it a lifetime of seconds (rather than the fraction of a second a lightning strike lasts for).

Several months later, Martin came back from one of his trips to Washington with a contract from the US Air Force for me to research ball lightning. I presume the US Air Force were interested to be able to make ball lightning and use it in the Vietnam War to scare the Viet Cong!

But there was a problem with my “hot air” theory: hot air rises and ball lightning does not generally rise. In 1969, after the contract period had expired, my colleagues and I concluded we still had no idea what ball lightning was.

Yet we wrote a paper, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research, entitled Toward a theory of Ball Lightning, in which we explained ball lightning could not just be hot air because hot air rises.

Lighting up the house

While many sightings of ball lightning have been made outdoors, it is also seen inside houses. In fact a recent French survey of 350 sightings in France found far more observations of ball lightning inside houses than outside (181 to 94).

Perhaps even scarier, ball lightning has been seen inside of aeroplanes.

Luckily, it seems the ball lightning that appears inside of houses and aeroplanes is harmless and no injuries have been reported. I’ve heard one report of ball lightning in a plane passing right through or around an air hostess as it travelled down the central aisle of the plane.

(By contrast, outdoor ball lightning has been seen to initiate very damaging lightning strikes.)

So how do these balls of lightning get inside houses and aeroplanes? And why does ball lightning almost always move?

People claim to have seen ball lightning entering a house through a closed glass window, yet subsequent examination of the window reveals no damage or even discolouration of the glass.

There have been hundreds of papers written in scientific journals speculating on these issues, variously assigning the energy source of ball lightning to nuclear energy, anti-matter, black holes, masers, microwaves … you name it.

A recent theory (besides our own) about ball lightning – published in Nature in 2000 by John Abrahamson at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand – is that ball lightning is a ball of burning dendrites (branched projections) of silicon fluff formed after a lightning strike vaporises material from the ground.

But it seems impossible that such a mechanism could cause ball lightning inside a house or aeroplane.

New and improved

The new theory about ball lightning that my colleagues and I have published is unlike any before it.

We propose ball lightning is powered by ions (charged particles) formed in the atmosphere, particularly from lightning, where columns of ions kilometres in length are produced from a lightning strike and “stepped leaders” (paths of ionised air).

In this way, ball lightning does not “pass through” closed glass windows, but is formed on the inside surface of the window by ions piling up at the outside surface of the window.

The piled up ions on the outside surface of the glass – which is an electrical insulator – increase the electric field on the inside of the glass, and can initiate ionisation – that is, the creation of charged particles.

Charges of the opposite sign to those outside on the window will be attracted to the inside of the window leaving a charged sphere of plasma free to move away from the window. This discharge is ball lightning.

Using the conventional equations for electron and ion motion in an electric field we were able to predict such a ball-like structure from a stream of ions impacting on glass.

In this way, we’ve explained (we believe) the principal mysteries of ball lightning. The energy source is ions left in the atmosphere after a lightning strike. The roughly ten-second lifetime of ball lightning can be explained as the time taken for ions to be dispersed to the ground.

The ball moves due to electrical forces from other ions that have collected on insulators, such as those that exist on the walls of rooms or aircraft. For instance, ions from the ball lightning discharge can collect on a plastic or wooden surface if the ball comes into contact with it, repelling the ball and giving the appearance of “bouncing”.

Creating ball lightning

Of course, the definitive proof of any theory is experiment. What we need is an experiment to actually reproduce ball lightning in a controlled way.

Several of the observations in aircraft have been when there was no evident thunderstorm. We postulate that the ions in this case were produced by the aircraft’s radio antenna.

If this is true, such experiments for the production of ball lightning should be possible, independent of the power sources of natural lightning, which typically generates up to 100 million volts.

If these experiments come to fruition, it is highly likely that, in the next few years, the long-standing mystery of ball lightning will be definitively solved.

No comments:

Post a Comment